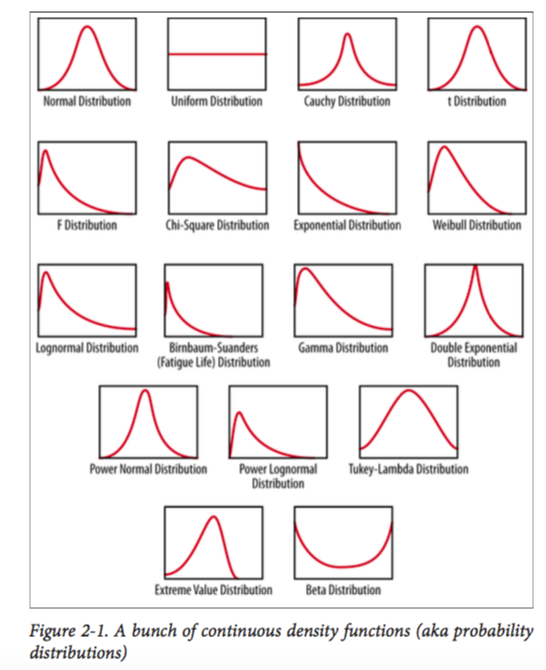

I was reading the book Doing Data Science this morning. There was a small section about probability distribution where I came across the picture in the banner. The purpose of the picture, the author wrote “to remind that they only have names because someone observed them enough times to think they deserved names.” Then she briefly explained how people observed data generated from natural processes, noticed the recurring patterns and built mathematical model to represent the data.

My article had nothing to do with data science or statistics. What I wanted to say was the author reminded me something that I never thought about models. Models are not golden laws that come out of thin air. They are there because of our attempts to understand the nature of reality. They act as lens of visions and skeletons of thinkings. Without models we can’t connect the dots in the chaos.

Learning the models is important when you start to study a new field

Before I started my digital marketing career in 2012, I was a product manager. The sudden change was a strike to me. Things that I had learnt about building product didn’t help me to sell the products. I felt disoriented and were easily carried away by the chaos of online information. I literally read a blogpost of top 50 online marketing tactics and tried out them one by one: SEO, PPC, social network, viral video, user community, newsletter, etc. Months passed, but nothing happened, except that I was mentally and physically drained out by all the activities.

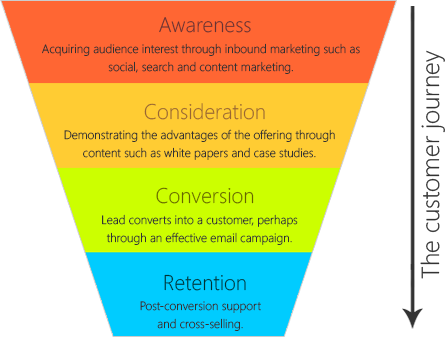

A few more months passed, I started to get good at some tactics, but I still didn’t know why I was doing them, especially I couldn’t connect them together to achieve my goal. This condition didn’t get any better until one day I came across this picture: the marketing funnel model, and suddenly everything became clear. I realised how I could align my activities with different stages of the model, and what I could do to make the funnel wider. Later I learnt that there were many digital marketing models out there and the funnel model had its limitation. But the way that this simple model helped me demonstrated the importance of having a model. No model is absolutely right. A model, even though it’s limited, can help us to see patterns in chaos, and when we see patterns, we know where to put the effort.

Companies can also use models to help people align their visions and make decisions

A company’s value statement pays this role. A successful value statement should be able to help employees make decisions, and help clients understand why certain decisions were made. I used to work in a company, whose value was “Simple and reliable”, which I found very practical in guiding my everyday work. Because it told us that the company cherishes simplicity against complexity, and encourages us to trust each other. We worked on making the product, the process and the relationship simple and reliable. It did a great job to help us cut abundant features and useless meetings.

I took this easiness for granted until I joined another company, whose value was “Happiness, sharing and rewarding”. I could say without hesitation the statement is right, but I didn’t know what I could do with it. I could’t get things done by saying “that makes me happy”, or decided to cancel a campaign by saying “that’s against sharing”. The value statement was great but completely useless to guide everyday work.

I’m not judging the right or wrong of these values . I meant a successful value statement should work as a model: telling how things work in the company so people can align visions and make decisions more easily.

Another thing to remember is that a model is just one way to interpret facts, a facade of the reality

You need to have lots of them from multiple disciplines to understand the world better. As Charlie Munger’s warning about having only one or two models: the nature of human psychology is such that you’ll torture reality so that it fits your model, or at least you’ll think it does. To the man with only a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.

This happens all the time to me, usually when I meet a new theory from a book. After reading Lean Start Up, I found the idea of MVP is genius. I started to spot MVPs everywhere, and many things that I could test on. I tested the lean way on lots of things: marketing, analysis, relationships, even cooking. The enthusiasm went out control until I realised the MVP model has its limitation and it isn’t always applicable to the other fields. Although testing the boundary of a model has its positive aspect, it can be dangerous if you don’t know many other models, in which case you are just holding a hammer and looking for nails.

No model is absolutely right. Each model can be genius solution in certain context, but completely useless in another context. To make models useful you need to know them well and practice using them a lot. My advice? Have a curious heart. Learn different models from multiple disciplines. Practice them and test their boundaries. Keep an open mind and accept that odds can happen.